Last updated: 10 May, 2025 @ 12:11

A new study involving lifeguard records from a number of UK beaches of people experiencing weever fish stings is helping scientists learn more about impacts of the environment of coastal fish populations.

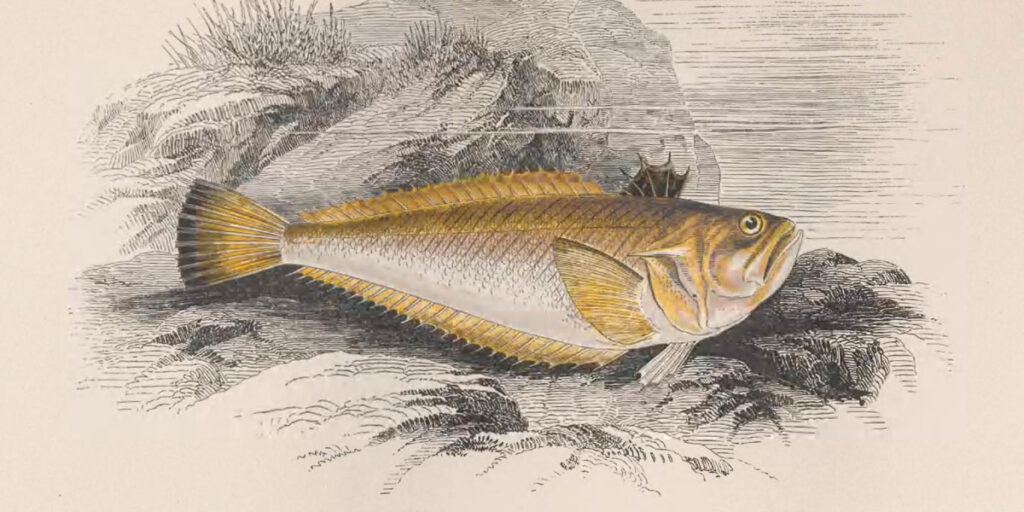

As we wrote about in our blog post Weever woe on the south coast: in search of the bouillabaisse, weever fish are best known for migrating into the shallows around the UK every summer lying hidden, half-buried on the seabed waiting to bring misery to small crustaceans, fish – and paddling children (and adults).

Speaking from personal experience, the searing pain inflicted by the weever’s venomous dorsal fin is unpleasant – and that’s putting it mildly.

However, a new study has used records of stings recorded on beaches covered by RNLI lifeguards, stretching from Burnham-on-Sea in Somerset, around the north and south coasts of Devon and Cornwall to Exmouth, to provide one of the most detailed investigations of how fish populations vary in time and space, in relation to environmental conditions.

Key findings: Environmental conditions and weever fish behaviour

For the study, during daylight hours over the space of almost eight months, lifeguards compiled two-hourly estimates of the number of people engaged in different activities (e.g. bathers, surfers) on beaches.

They also recorded the number of people requiring assistance after being stung by weever fish, and analysing that – along with environmental data – provided scientists with a ‘unique window into how environmental conditions affect fish populations’.

The study found that between April and November 2018, when the records were compiled, lifeguards observed a total of more than 5.5m people across the 77 beaches.

The study also showed that 89% of all stings occurred during the peak summer months of June, July and August, with smaller increases coinciding with the Easter and spring half term holidays. Stings tended to occur most often around the times of low tide.

Overall, the scientists say, ‘weevers seem to be more active in the shallows of beaches under the same conditions that humans prefer – sunny, calm summer afternoons at low tide’ – which is great news for us all…

‘The positive in what can be a painful experience’

Published in the journal Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, the research was led by former masters student Ryan Hepburn and lecturer in Marine Biology Dr Benjamin Ciotti from the University of Plymouth’s School of Biological and Marine Sciences.

Dr Ciotti said: “Coastal waters are incredibly dynamic environments and the first in line to experience human impacts.

“Against that, it is hugely important to understand which habitats and conditions different species require, so we can manage our coast in ways that sustain healthy fish populations.

“Detailed information on how fish use our coasts, however, is just very hard to come by. We can spend all summer doing surveys just to get a few data points,” he said.

“Given the huge numbers of people who visit our beaches each year, the records compiled by the RNLI through the summer months are truly unique – I am not aware of any other dataset that provides such a detailed picture of habitat use in a fish species, anywhere.

“The positive in what can be a painful experience is that this is really helping us to understand what drives variation in fish populations inhabiting the shallowest waters which overlap most with humans.”

The weever: understanding the hazards

Dr Sam Prodger, head of data at the RNLI said: “It’s important for us to collaborate with partner organisations, including universities with their academic specialities, to enhance our understanding of the various hazards in the environments where we operate and to keep people safe.

“The outcomes from this work will help us understand the drivers behind one of the major time demands on our lifeguard service and examine the potential predictive factors for future years.”

Share this Fish Face Seafood Blog article.